Breaking the rules: Magical secrets of game design | Pocket Gamer.biz

Creating a memorable and successful game experience is no easy feat, not only do developers need a solid core idea, they also need to execute it well and present the experience to players in a way that keeps them hooked and becomes memorable. In a sea of other video games, standing apart is difficult, yet by breaking down the rules of the game and accessing how each one impacts the player, something magical can be created.

In this guest post and in advance of his free webinar on Tuesday, August 15, author, CEO and games industry insider, Oscar Clark shares some top tips on game design to drive retention and create memorable experiences for players.

There are some amazing designers out there who have an encyclopaedic memory for each moment in the vast legacy of games. Whilst I wish I had that ability, I try to think about the underlying principles – and how we can apply them to make magical experiences.

Even the most elaborate game world with the most realistic characters, gameplay can be reduced to simple principles

Oscar Clark

There is a kind of magic trick that game designers pull off that I’d argue has some parallels with the magical acts of folks like Penn & Teller or David Copperfield. Both Magicians and Designers have to present a scene with gimmicks and tools, setting up the expectations of what should happen and subverting the audience’s observations to create entertainment. Even the most elaborate game world with the most realistic characters, gameplay can be reduced to simple principles. There is usually some object with rules on how we interact with it and how we apply (or even subvert) those rules to overcome challenges, sometimes nicely wrapped up in a narrative arc. This is a kind of “sleight of hand” in which we create the impression of an immense world when in reality, it is little more than smoke and mirrors, or should I say objects, triggers and collision layers. Players (and our magician’s audience) aren’t expected to appreciate the maths, development time and forced perspectives we use to create that illusion we just want them to enjoy the game.

Thankfully there is no such thing as a Magic Circle for game developers, so I’m safe to try and share some of the tricks that I’ve learned that I find amazingly useful to make any game from simple mechanics and a framework that helps me build retention (and even design monetisation) always focused on how we can delight players.

Making rules to break

For the purpose of this article, let’s start by thinking about games as a set of rules. These are the fundamental principles of how we interact in the game world. It can be how we move, what happens when we tap a button, what seeds grow into what resources, etc. These laws need to be consistent, or the game falls apart.

From that, we determine a set of simple, predictable actions that work within those laws. Shoot a gun, drive faster, move a block, etc. These actions will have their limits, how much damage, how much fuel or how fast. But the magic comes when we reveal how these rules interact with each other to confound expectations. Whether it’s a puzzle, shooter or platform, any game benefits from creating moments where to succeed, the player has to find how to use the space between the rules and limitations in ways that were not immediately obvious.

This can be as simple as the drift mechanic is a racer or strategic use of combo moves in a brawler. It comes in the differences in feel between a shotgun (low rate of fire/large damage) and a submachine gun (high rate of fire/low damage). The magic system in Wildermyth, for me, is a great example as we use items in the world as the source of your mage’s power that not only defines the kind of effect but can also change the tactical map.

Tap into the potential

The first thing I tend to consider is how to use simple interactions like tapping on a screen. Tap on a touch device has a lot of potential as it not only can apply to any UI element on the screen (well within reason given folks like me have quite stubby fingers), but we can play with how that interaction can be used.

We can tap, tap and hold, hold and move around the screen, hold then release, double tap, tap to a rhythm, tap against a timer, etc. We can add swipes or multiple fingers to the mix to add even more options. These can be used to target objects or enemies, as controls for power meters, and to respond to quick-time actions. This is great as a tool kit for a designer to play with, but try to keep the player’s context in mind. Like a magician doing close up magic, we need to keep their focus where we want it. We want them deep in the act of play, not having to dissect how the game works or being preoccupied with other factors. So if you make it impractical to hold a mobile phone and use the same hand to interact with the game, you break the conceit, and your audience churns out in frustration.

Confounding Expectations

Once the core principle of how and what we do is established, we can get playful

Oscar Clark

My next step is to consider how the interaction drives forward gameplay. Am I selecting objects and moving them? Am I targeting enemies? Am I finding the optimal path? How does that translate to firing an upset avian at a pile of porcine enemies or matching colourful sweets that will explode if I make patterns?

Once the core principle of how and what we do is established, we can get playful. In fact, one fantastic designer I know uses a test when recruiting that I find illustrates this perfectly.

How many types of health potion, with an equivalent value to the player, can you design adjusting ONLY health and time as variables? Can you come up with at least ten distinct variations?

I find this way of tackling design choices so helpful to rethink how a given ruleset should work (and how to turn its limitations into delightful ways to subvert expectations). For example, any action in a game can have a preparation/effect and cooldown components as well as having some relationship between position in the game and timing. Information supplied in a game can be spread out over the time you play or, indeed, geographically across the game world. This means there are clues, but it’s down to the player joining the dots. We may even deliberately give incomplete or untrustworthy information – depending on what we try to achieve in the design. We can also apply cost to any action in terms of stamina, resources, and charges. That, in turn, leads us to think in systems that include thinking about capacity, regeneration rates, resource gathering, etc., all of which can deliver game activity, feel and tone.

That’s a lot to take in, but each designer interprets the application of rules in ways which make sense to the player experience they are looking to create for example:

- Fighting Game: How much delay (animation) is required for a warrior to prepare their enormous great sword, how does that relate to the damage done and time to recover for the next hit.

- Animal Game: How much attention (feeding/petting) do we have to do to get a friendly woodland creature to warm to the player, and what benefits can be harvested from them once friendly.

- Racing Game: How do we use movement delay, sound effects, vehicle speed rate of change, road handling to demonstrate the feel difference between a truck and a sports car – and what are the offsets in terms of how much damage the vehicle can take or fuel used.

Building in Layers

So far, so good, but how can we combine the different activities, rules and interactions to create sustainable gameplay? Like many designers, I think in loops and for me, there are three levels we need to consider. This starts with the Mechanics themselves or what we actually do in play, and I look at that in four stages:

Adding a challenge should help build a sense of tension

Oscar Clark

Start Condition: What do the players immediately see, and how do they identify themselves? Part of my thinking is how we expect players to start emotionally, and generally, I expect them to be relaxed, anticipating what is to come.

Challenge: We need to clearly communicate the challenge players are expected to overcome. Reach a location, avoid the monsters, collect 15 gold, etc. As well as ensuring we are communicating what the player needs to do and what success at that stage looks like, we also need to look at how this impacts their emotional perspective. Adding a challenge should help build a sense of tension – will I be able to do this – but at this stage we still want to retain a sense of anticipation as they have to act.

Resolution: Next step, players do the things. We expect them to use the interactions we have explained to do what’s needed to resolve the challenge. This becomes more interesting where we have subverted those rules, playing a kind of sleight of hand that confounds expectations – without changing the predictable ‘Laws’ we have already established. For example, in a fighting game introducing an opponent that can dodge the heavy great sword and strike with a lighter, faster rapier – even if it doesn’t do as much damage when it hits. We want to leave players feeling smart because they understand how to combine these laws for a new result. If we can leave room for skill and grind to be meaningful with relative measures, list time or score, rather than just a binary pass/fail, all the better. In other words, can they complete the challenge faster, in fewer moves, or with a greater score. This opens you up to leaderboards, longer term play progression and competitive play. In this stage, the emotional impact we aim for is to retain the tension introduced by the challenge while creating a ‘Fear of missing out’ where the successful completion of the challenge has a meaningful impact.

Always try to balance making the rewards appealing and creating reasons to continue playing through a sense of unfinished business

Oscar Clark

Reward: Once the player is successful (or indeed if they fail), we need them to understand that they have completed the expected behaviour and get some recognition for that. They need to have a chance to rest and reset, to feel more relaxed after the tension. We need the impact to be meaningful, but where they fail, not punishing. Sure, punishing players is a thing that can work in some games, but it can cause folks to churn unless managed carefully. Equally, granting points or gold stars is a weak form of motivation. Instead, we want to focus on intrinsic rewards supporting mastery, autonomy, and completion. We can also add more extrinsic rewards marking missions as complete, achievements and trophies – yes, even gold stars, but they become more meaningful when linked to intrinsic motivation. One lesson I’ve learned is that when we look at rewards, we need to retain a sense of ‘Fear of Missing Out’ to encourage players to feel that there is more to unlock. So I always try to balance making the rewards appealing and creating reasons to continue playing through a sense of unfinished business. This even applies to players who fail, giving them some recognition for their effort and helping them feel that they have a chance to nail it next time.

For many, that’s all, and the game is done. But for a more sustainable experience, we need to go a couple more steps. The first of which I call the Context loop, which is how we create a sense of purpose and progression to keep players wanting to do more. Again the Context loop has four stages:

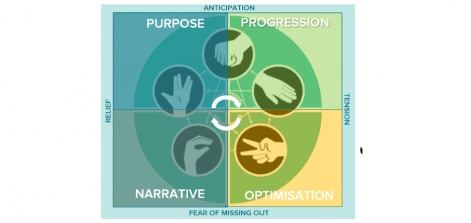

Purpose: This is really the fundamental of why we are playing, and there are the overt narrative objectives, but also the subconscious real world motivations for choosing this game in the first place. Whilst a Zelda-like game may essentially come down to rescuing the Princess, the state switches between relaxing exploration, exciting combat and demanding puzzle solving. This stage mirrors the ‘Start Condition’ of the mechanic loop. It’s about the setting of expectations, albeit about the whole game rather than the specific scene, and we expect players to enter with a relaxed mind state and anticipate the playing experience to come. We must ensure that players clearly understand what to expect (with room to appropriately subvert that expectation). An essential part of this is a contract between the designer and the audience of the Laws of the world that won’t change.

Progression: Setting out longer term goals that run between multiple play moments is essential and parallels the ‘Challenge’ stage in that we must set out what is expected. However, this can often involve more ambiguity and some associated activity for the player to discover. What is important is that players can instantly understand their progression to date and have a target for the next stage and the next. Sometimes this can be seasonal or endless, but the next goal needs to always feel completable and attainable. Again, just as with the Challenge stage, we want to sustain the anticipation while building a sense of tension.

Optimisation: Something I think we don’t talk about enough is the joy of optimisation. As players, we find the most streamlined ways of completing our objectives. I guess the most extreme version of this is Speed Runs, but working out the best patterns or habits of play is a meaningful aspect of the game. I think of this as a longer term equivalent of the Resolution stage. Something which we adapt/change over multiple players, especially as the layering (subverting) of rules affects the efficient play in each new level. Creating a sense of Tension and Fear of Missing out at this stage is key. In some games, this can be incredibly engaging, where we can find a way to contrast the needs of the immediate gameplay against what’s needed for the longer term progression.

Narrative: For me, the payoff for a player over the longer term comes from the narrative arc in the game. This is a combination of the revealed backstory of the game, either through linear release or some kind of epistolary discovery and the personal experience of play over the whole experience. Most narrative games have a beginning, middle and end, but we don’t have to be limited to that. Games don’t have to follow the Movie model at all. We can learn a lot from how long-running TV shows and soap operas deliver sustainable, lasting and compelling stories that adapt, change and grow with us for years, even in the case of shows like Coronation Street and Days of Our Lives for decades. The key, in my view, just like rewards, is for the narrative to relieve the tension and still leave room for Fear of Missing Out.

We could stop there. But there is one last loop. Something that sits outside of the game itself – and perhaps the greatest magic trick we can play as game designers. Just as the audience is a key part of what makes a magic trick work on stage, social engagement can transform a game experience – that’s what I mean when I talk about the Metagame. Again we follow the same pattern with four stages:

Lifestyle Fit: Ok, I know this sounds leftfield, but bear with me. If we expect players to engage with our game more than once, we need to consider where they are in the real world and how they will choose to play. We tend to play PC games in a ‘den’ or office separate from others. We tend to play on consoles in bedrooms or living rooms on big TVs, and we tend to play with mobile phones wherever we are, including in the living room, whilst someone else in the family uses the TV or, indeed, on the toilet. As with the Start Condition and Purpose, we need to set expectations, which usually comes from a relaxed state combined with anticipation.

If we expect players to engage with our game more than once, we need to consider where they are in the real world and how they will choose to play

Oscar Clark

Collaborative: Despite online multiplayer being a thing since the late 90’s (arguably since 1984 – I was playing Shades on Apple IIe in 1984), we often don’t pay enough attention to social design. Collaboration isn’t just about Coop play. This is about how we use social media, create UGC, and share fan wikis of our favourite games. When playing Tribal Wars (a web game), we chose the most obscure chat service to coordinate our attacks to avoid hacking/spies discovering our plans. This meaningful connection creates a sense of ‘US’ that is a powerful motivator. Even having a ‘Wanderer’ (a real player who only contributes a power-up to your play) can add a meaningful sense of collective endeavour. This is more of a layer than a stage but happens to also benefit where we can use this to build anticipation while ramping up the tension but pitting us against a common enemy (or ‘Them’).

Competitive: Not every game has to be directly competitive, but even in games like Farmville, at a social level, the ability to show off matters. I’m so often shocked that a game reliant on cosmetic content doesn’t allow players to show off what they have earned (and why those items are meaningful). The ability to demonstrate your abilities, persistence, creativity and personality can be hugely impactful in any game, especially when we build on top of a shared sense of identity – the ‘US’ we try to develop through Collaboration – not least as this can help mitigate against some of the risks of toxicity. And, of course, Competition has a unique way of building both tension and Fear of Missing out.

Zeitgeist: I use the term to describe the spirit of the age to describe creating experiences for the player and the player’s audience. Whether that’s showing off to friends or making a massive following on a social platform. For me, the key to building community and even esports comes from understanding how the game moves an audience from anticipation to fear of missing out and between relief, tension and back again.

Keeping the secrets

Everyone has a different way of looking at game design. I’ve deliberately avoided giving specific examples as they age so fast. Instead, I hope I’ve got you thinking in systems. How can you take a simple idea like a health potion and create crazy variations that feel distinct without introducing new rules? How can we apply different ways to interpret a simple interaction, and how, through layers, can we make the game, its world, and the stories we tell each other through play feel immense? My top tips for any designer on any game come down to this.

- Create clean Laws of the game world that have defined limitation

- What emergent properties arise when you layer those rules

- How can you play with interactions so players can benefit from skill or grind

- Build an experience in layers (Mechanic / Context / Metagame

And don’t miss Oscar’s free webinar on Tuesday, August 15 2023. Details and tickets here.

Edited by Paige Cook

About Oscar Clark

Oscar Clark has been working in games since 1998 and literally wrote the book on Games as a service. He is CEO of Fundamentally Games LTD, a publisher of living games committed to transparency and genuine partnership with developers. He is also a contributing editor for PocketGamer.biz.

About Fundamentally Games

Fundamentally Games is a modern publisher focused on games with live operations. They publish under the label, Jetpack Collective. www.fundamentally.games